Tony Vanderwarker has just released a new book, I’m Not From the South But I Got Down Here As Fast As I Could – How a Connecticut Yankee Learned To Love Grits and Fried Green Tomatoes And Lived To Tell About It. I caught up with Tony to get a candid look at the author’s background, the new book, the writing process and life in general.

Tony Vanderwarker has just released a new book, I’m Not From the South But I Got Down Here As Fast As I Could – How a Connecticut Yankee Learned To Love Grits and Fried Green Tomatoes And Lived To Tell About It. I caught up with Tony to get a candid look at the author’s background, the new book, the writing process and life in general.

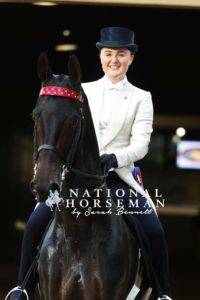

Keswick is full of diversity. Historic farms with manicured road fronts flank the cottages, bungalows, and the more modest dwellings. It has working people, stay at home people, business types, caregivers, families, white-collar types, and a few billionaires. The friendly people in Keswick come from near and far, from the ‘North’ and the ‘South,’ some from other places and some have been here all along. Home is comfort – it is where you can be yourself, let your guard down and just relax. The ‘community’ where the stories are born, the bonds are made, and you build a life with ‘your’ people. The parties, some quite famously, are the melting pot for the young and old, the working and the leisure types. All the faces are familiar, whether you are at a backyard pig roast on Clarks Tract or in a barn transformed in honor of ‘the big’ night of the moment. While waking up in the Keswick world, at times, the rest of the world seems so far away. We come to Keswick and find a guy next door. In case you’ve missed him, his name is Tony Vanderwarker.

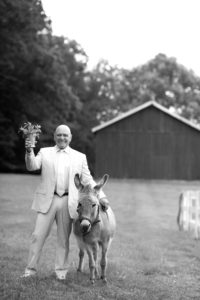

I met Tony to do this article at my studio at Liberty Park, a former factory building, in Gordonsville, located just behind a Food Lion located in a quaint small town strip mall with a menagerie of mostly eating-places. The plant, an all too typical modern American story, closed down after the lace fabric they produced could be done for less outside of the United States, three shifts of 625 people lost their jobs nearly overnight. He quickly found my space amongst the in progress rehabilitation of the factory to smaller flex spaces, he has an unmistakable confidence, with a street smarts sensibility – familiar and highly self-aware. He is 70, sharply dressed but mostly casual, has a distinctive style, a warm smile, a kind soul and shaves the stubble from his head every morning. We arranged some comfortable seats and sat down. He looked at me and smiled.

I met Tony to do this article at my studio at Liberty Park, a former factory building, in Gordonsville, located just behind a Food Lion located in a quaint small town strip mall with a menagerie of mostly eating-places. The plant, an all too typical modern American story, closed down after the lace fabric they produced could be done for less outside of the United States, three shifts of 625 people lost their jobs nearly overnight. He quickly found my space amongst the in progress rehabilitation of the factory to smaller flex spaces, he has an unmistakable confidence, with a street smarts sensibility – familiar and highly self-aware. He is 70, sharply dressed but mostly casual, has a distinctive style, a warm smile, a kind soul and shaves the stubble from his head every morning. We arranged some comfortable seats and sat down. He looked at me and smiled.

Tony grew up in quintessential northern suburbia, Connecticut, with working parents who wanted a better life for themselves and their two sons. A young Tony would follow the course his parents set for him. He attended the highly selective, preparatory high school for boarding students, Phillips Andover in Massachusetts. He was being groomed, “set up to meet the perfect blond haired Daddy’s girl” he quips, with the wealthy family and get the comfortable life. Tony thought, “what is all this business,” knowing deep inside that this doesn’t feel right. His parents befriended others who had something that they desired themselves, social climbers, who thought the rich walked on water. Among the many things imparted from parent to child, they described to Tony and his younger brother a South that was full of hillbillies – not their type of individuals.

Tony grew up in quintessential northern suburbia, Connecticut, with working parents who wanted a better life for themselves and their two sons. A young Tony would follow the course his parents set for him. He attended the highly selective, preparatory high school for boarding students, Phillips Andover in Massachusetts. He was being groomed, “set up to meet the perfect blond haired Daddy’s girl” he quips, with the wealthy family and get the comfortable life. Tony thought, “what is all this business,” knowing deep inside that this doesn’t feel right. His parents befriended others who had something that they desired themselves, social climbers, who thought the rich walked on water. Among the many things imparted from parent to child, they described to Tony and his younger brother a South that was full of hillbillies – not their type of individuals.

In school, Tony was a frustrated artist, deeply embedded in this life but not of his making – not yet able to break out of the rut. At Andover, his advisor works up a Morehead Scholarship opportunity for consideration in North Carolina. Tony explains, “I felt like, was that all I was capable of, a school down in the South, in North Carolina, where is that exactly, and is this all this guy thinks of me?” He ends up at Yale, and for the proud parents, all seemed to be on track. Tony explains he had an epiphany during his sophomore year, bagged his mother’s vision of his life and quit Yale. Ambitious to flourish in the change up, Tony joins the Peace Corps and heads to Africa. Spends a year there and gets inspired by film then back to school, this time at NYU. In a cinema program, Tony flexes his creative muscles, finds comfort in his skin, graduates with a degree in Cinema and makes a full-length theatrical film – it is the late 1960’s.

Next up, sick of freelancing in the movie business, he moved to Chicago to get into advertising. He had a rapid rise in the ad biz first as a copywriter, then as creative director where he worked on McDonalds’ “twoallbeefpattiesspecialsauceletture cheese”, “Big Mac Attack” and then, when he started his own agency with two partners, did “Be Like Mike” for Gatorade. During a visit to Chicago by his parents, Tony was walking them around his two-hundred person, $180 million in billings agency when his mother reverted to form and asked, “Don’t you miss being back at the agency that was listed on the New York Stock Exchange?” His father quickly reminded her, “But Patty, he owns this whole place.”

In Chicago, life is good, business is booming, and Tony meets Annie, they get married, and life is even better. Annie has two young boys of her own, they marry and have two more kids together with a house in the suburbs – a blended union, a modern fairytale. The partners, at the ad firm he helped to create, unexpectedly execute the buyout clause, which lands Tony on the sidewalk. So the question was, “Do we stay or do we go?” Stay in familiar territory or strike out and try something new. The moment came, albeit not entirely but surely it was a catalyst – while Tony and Annie were walking in the neighborhood they spot their two younger kids sipping fancy hot drinks in the window of the Starbucks along the walk to their school. Too much sophistication too soon, they thought. They decide to move to Charlottesville and take advantage of Annie’s family there for some support.

The indoctrinated Northerners settle into the Charlottesville area, first to Ivy then to Keswick. Setting all his predispositions aside, Tony embraced the South, the warmth, and fellowship of its’ rich culture and roll-with-it ways. And now, circuitously, they are in the South, and unexpectedly it would change them all for the better.

Tony Vanderwarker has written a memoir, dedicated to all he cherishes about his life changing move to the South. He quickly realized upon his move to Virginia, the South wasn’t filled with mountain people but instead he found the simpler way of life he was so eager to embrace for his family and his well-being. His ad agency partners might have given him one of the best-unwelcomed opportunities, despite the forced retirement and resulting relocation; a familiar story for many people in America today. For Tony, the South was warmer, in all the ways this word invokes, and in contrast made the North seem cold and distant. Here others are accepting of your way of life; there is little judgment and if there is it considered irrelevant.

The book brings Keswick to life; full of stories that were begging to be told. Tony explains, “My book is a love letter to Keswick. Not only is Keswick stunningly beautiful, it’s a marvelous place that asks to be brought to life. Here we have celebrities and billionaires living side-by-side with hairdressers, farriers, and farm managers. Tony and Annie offer cottages on their farm to the Airbnb service; the guests are amazed – they come from all over the world to see and share the magic of the area. The South is changing. We talk about the fancier foods, with sophisticated flavors that pay homage to their origins but now put the food on the world map. The greater Charlottesville area has broad appeal, with the downtown mall, world-class museums and living history experiences and exhibits at Monticello, all just a few miles apart.

The genesis of Tony’s book was the incredible response to his column “Only in Keswick” in this paper, where Tony began to tell his stories of the incredible people and amazing things that happen here. “You ought to put these together in a book,” more than one reader said. Stories like the ones about Chita Hall, who kept lions and bears (even reportedly an elephant) on her property, who would give cans of pop to her pet bear Betsy and delight in watching her perch on her haunches and glug the soda down. Or her husband Chet who trained his parrot to say salacious things. Once an encyclopedia salesman came to the door, the parrot invited him in and then said, “Sic him” to the Doberman who chased the terrified guy off the farm. Or the business tycoon who hits and kills a huge buck with his truck right in front of his farm and leaves the carcass to get help to dispose of the critter, Quickly returning, they find in the meantime, someone had stopped and used a chain saw to hack the head off the carcass in order to take the rack home for themselves, leaving the headless body behind.

The stories are true Keswick, wild and wonderful. Tony adds, “Everybody appreciates the leveling factor; no one looks down on anyone. The book is good-natured with the sense of ‘Isn’t it great to be living in this amazing place?'” Many of the stories are outlandish and could only happen here. For instance, the wedding that got rained out by bats dropping from the ceiling. One of his neighbors says, “There are no secrets in Keswick.” The writer feels that people in Keswick willingly share stories, tribulations as well as personal heartbreaks and hardship. “When someone gets sick or has a tragedy, the calls are made, the food starts to flow and countless, ‘How can I help?” calls go out.” This is quintessential Keswick, very Southern, and the way it has been done here for generations.

Tony has written millions of ads and a bunch of books, but it took him twenty years to get his first published. He has published three, Writing With the Master, Sleeping Dogs and Ads For God. The writing process seems to come naturally for Tony; it suits his seemingly systematic ways. He writes, standing up, for three hours in the morning, like it is his job, just five days a week and shoots for a thousand to twelve hundred words per day – he admits some days are slower than others.

Using a computer, he keeps the ideas flowing without getting hung up on shaping the story, which comes later. The ideas rush in for the books, sometimes while driving in a car, or at a cocktail party and they often don’t flesh out as quickly, they have to ruminate. Tony explains he is not a plotter; some writers he admires, like John Grisham, are outline-driven and develop characters with a clear path from beginning to end. Tony wings it, characterized by writers as pantsing (putting your pants–and what’s in them–in a chair) and writes without an outline. “You end up hitting the delete key a lot,” he says, “but it’s the way I feel most comfortable writing.” He says he’s become good at editing, “Bad writing is like hitting a wrong note or farting in church. I sniff ugly stuff out as fast as pigs do truffles.” Typos bug him, as they do all writers, “They are like ants, you think you’ve swatted them all and then another crawls out. I dread seeing them in my published books because I see them all the time in others.” He dismisses “writers’ block,” saying, “the writer creates it so he can destroy it.” Tony gives aspiring writers the following simple advice, a quote from Thomas Edison: “Many of life’s failures are people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up.”

“That’s my motto when it comes to writing, ‘Never give up; you never know when you’ll find your pay dirt.'” Tony started writing funny stuff, struck out a bunch of times, then tried non-fiction, Writing With The Master, then a thriller, Sleeping Dogs, but found humor (with Ads For God) was his niche. “Hiaasen, Dave Barry, and David Sedaris are my idols. But I get a kick out of some of my stuff too. And I absolutely love it when someone comes up to me and says, ‘Your article made me laugh my ass off!’ That’s one of the great rewards of writing for you guys (Winky and Colin at KL). People come up to me at the post office, at parties, it really brings my writing home.” Tony started writing stories for I’m Not From the South about three years ago. “When the book finally does come out (Nov. 17), it will feel like I wrote it ages ago.”

Our pantser is already working on his next book, titled, Visits to Venus, How a Man From Mars Can Survive the Marital Wars. Tony has fun playing with the differences men and women have as displayed in driving, parking, making beds, loading the dishwasher and other life-changing experiences. An excerpt from the new book was published recently in Keswick Life titled, ‘I Married a Garden Club’ – the response was immediate, he hit a nerve with husbands from all walks of life. Tony radiates infinite gratitude to have had these experiences with the books, the very personal stories and the people he meets in the process.

We have all heard it takes a village to raise a kid, well there are some people in Tony’s camp worth a mention. First, his family that enjoys his writing and are jubilant with him doing it. One son, a graphic designer, did the first three book covers. In general, they accept Tony and his creative tendencies as a way of life for them – each creative in their individual endeavors perhaps as a result of Tony’s example in his determination to release the caged and frustrated artist he recognized in himself so many years ago. Tony stresses that Annie, his wife, “is entirely on board with the writing, and that is great” and adds “the most important thing is she still laughs at my jokes.”

Tony uses Beta readers, known as a pre-reader or critiquer, a group of friends in his case; some who are writers as well. The group, which consists of mostly women, read his written work with the intent of looking over the material to find and improve elements such as grammar and spelling, as well as suggestions to improve the story, its characters, or flow. Done before public consumption of his material, the Beta readers are not explicitly proofreaders or editors, but serve him in that context. Mary Murray, in Charlottesville, designed the cover with a Grant Wood, American Gothic, feel with a bit of Green Acres mixed in. Sarah Cramer Shields, a local photographer, took the photograph. Duke Merrick is one of the people the book is dedicated to, as he threw the phrase out at a Keswick Hunt Club party in the intro to one of his songs, saying, “I saw a bumper sticker that read, I’m Not From the South But I Got Down Here As Fast As I Could.” Tony quickly scribbled it down, realizing it would characterize his book the way many titles don’t.

The publisher and publicist are keys to the success as it is their network of contacts that Tony uses to try to make the book stand out among the bombardment of eight hundred books or more published in the United States every day. He adds, “The publicist opens the world up to you, it is who they know as it is impossible to get on television and broadcast the message yourself.” Most well-written books that just don’t sell suffer from the fact that nobody noticed it, Tony comments “the headlines take over everything or sometimes it is just bad luck.”

His publisher, a small outfit in Mississippi, saw the potential in both the book and the title. Tony said, “Americans of any age, but particularly Boomers, are looking for alternatives.” And perhaps, I joke, a pitchfork and mint julep, too. He agrees and underlines the changing Southern culture as well as its more pleasant climate. His book has a memoir feel, a Year In Provence character, about the longing for something new and different (and maybe also cooler, cheaper and with more character). So far, he’s been pleased with the reactions, “If people like my Keswick Life stuff, they’ll love this.” And one of his Beta readers said, “I absolutely howled through the whole thing.” The Kindle edition is now up on Amazon and Tony watches the sales carefully, hoping that he’ll get enough before November 15 when it publishes, to qualify for Amazon’s bestseller list which catapults him up the Amazon ladder. If you are inclined to make an order today, I guarantee you won’t be sorry. In the meantime, Tony, who is always writing even if his hands aren’t on the keyboard, will be out there mowing the lawn listening to NPR or kicking back with Hiaasen’s latest in hand.