Editor’s Note: Warning! This story is a bit strange, as it begins as non-fiction and ends as fantasy, with a weird mid-70s TV pop-culture connection which the writer hopes the older folks will get, but the young’ns might say “whoa, this guy’s doin’ some bad stuff”. I hope you enjoy this as much as I did, and be sure to write in and tell it to Keswick Life and Charlie on what you think. – Colin D.

For this angler, no town is more misnamed than Last Chance, Idaho, the headquarters for fishing the famed Ranch Section of the Henrys Fork River. It should be named No Chance. When there, I rise confidently by 7AM – a most uncivilized hour for fly fishers – so that I can walk the two miles or so to the Islands, a lovely section of the famed spring creek, and arrive before other anglers and the wind, with the hopes of seeing a few noses poke through the glassy surface. Often there are noses, but they are attached to most diminutive bodies. Occasionally, across conflicting currents and in difficult lies near the banks, the noses and their appended bodies are substantial. But these noses are different, as they usually seem to be positioned over mouths that aren’t designed to open, at least for my offerings. And, the better rises seem always to be just out of my casting range and, magically, as I try stealthily to move toward them they move away at the same speed. I flail the water, spending much of my time changing flies, until invariably the wind comes up about eleven o’clock, creating a riffle, putting down the noses and driving me off the river to the supreme boredom of Last Chance, until the evening hatch starts. It’s the kind of experience that makes non-believers wonder why anyone bothers with this activity.

For this angler, no town is more misnamed than Last Chance, Idaho, the headquarters for fishing the famed Ranch Section of the Henrys Fork River. It should be named No Chance. When there, I rise confidently by 7AM – a most uncivilized hour for fly fishers – so that I can walk the two miles or so to the Islands, a lovely section of the famed spring creek, and arrive before other anglers and the wind, with the hopes of seeing a few noses poke through the glassy surface. Often there are noses, but they are attached to most diminutive bodies. Occasionally, across conflicting currents and in difficult lies near the banks, the noses and their appended bodies are substantial. But these noses are different, as they usually seem to be positioned over mouths that aren’t designed to open, at least for my offerings. And, the better rises seem always to be just out of my casting range and, magically, as I try stealthily to move toward them they move away at the same speed. I flail the water, spending much of my time changing flies, until invariably the wind comes up about eleven o’clock, creating a riffle, putting down the noses and driving me off the river to the supreme boredom of Last Chance, until the evening hatch starts. It’s the kind of experience that makes non-believers wonder why anyone bothers with this activity.

Ah, but there are consolations. The evening hatch, though typically yielding only an hour or two of fishing before dark, usually brings up more large fish, and I have frequently succeeded in hooking a few. And there was the après-fishing. So, I was saddened to read last year that the A-Bar had finally closed for good.

The A-Bar was a prototypical Western saloon. The only one in Last Chance and for another forty miles or more. It had the essential ingredients – a horseshoe shaped bar with a glass top covering hundreds of silver dollars, a coin deposit pool table accompanied by a few cues, one or two of which rolled straight on the table and still had their tips attached, a juke box filled with edgy pop stars like Merle Haggard and Little Jimmy Dickens, a television that got one channel poorly, dinette tables scattered about with plastic covered chairs embedded with last week’s salsa, and a clientele of local ranch hands, fishermen and their guides, bikers and their bimboesque babes slow dancing, and a few tourists who were lost on their way to Yellowstone Park. The food, red meat or Tex-Mex, mountain oysters or lamb fries, was better than decent, and my only complaint was the lack of draft beer and, in fact any beer that had the slightest hint of flavor or body, until Sam Adams appeared in bottles a few years ago. The A-Bar was welcoming to everyone –its vice and its virtue.

The A-Bar was a prototypical Western saloon. The only one in Last Chance and for another forty miles or more. It had the essential ingredients – a horseshoe shaped bar with a glass top covering hundreds of silver dollars, a coin deposit pool table accompanied by a few cues, one or two of which rolled straight on the table and still had their tips attached, a juke box filled with edgy pop stars like Merle Haggard and Little Jimmy Dickens, a television that got one channel poorly, dinette tables scattered about with plastic covered chairs embedded with last week’s salsa, and a clientele of local ranch hands, fishermen and their guides, bikers and their bimboesque babes slow dancing, and a few tourists who were lost on their way to Yellowstone Park. The food, red meat or Tex-Mex, mountain oysters or lamb fries, was better than decent, and my only complaint was the lack of draft beer and, in fact any beer that had the slightest hint of flavor or body, until Sam Adams appeared in bottles a few years ago. The A-Bar was welcoming to everyone –its vice and its virtue.

I also have a sentimental attachment to the A-Bar. Some of my favorite fishing experiences and fantasies began there. One night in the mid-90s I was sitting at the bar, quaffing a beer and pondering what was deficient in my personality or judgment, that I would commit so much time and effort to such an utterly hopeless activity, when I overheard the guy on the next stool say to the bartender “Tomorrow I’m cutting out of here for the Missouri. I just talked to my buddy who is up there, and he told me that the river is lower than it has been in years, you can walk the banks and wade everyplace, and the dry fly fishing is awesome.” I knew nothing about fishing the Missouri, but it sure sounded better than what I had going. So, I got some details from the guy and the next morning, instead of walking down river, I drove north to Wolf Creek, about four hours away. I had some great fishing and the Mo became one of my favorite rivers. I have returned nearly every year since.

Another night, I was sitting next to a young man and we got to talking about places that we had fished. He said that for the past two winters he had guided at a lodge in southern Chile called El Saltamontes. I asked him how it was and he replied “You know what ‘saltamontes’ means, right?”

“Yeah. Sure. It’s an Italian dish with veal wrapped in prosciutto and sage, cooked in marsala, over a bed of spinach. I prefer the version with a few slices of a hard-boiled egg on top, but what the hell does that have to do with fishing?”

He rolled his head back and his eyebrows went up to his hat. “You’re joking, no? Saltemontes means ‘grasshopper’ in Spanish. The Lodge is on the Ñirehuao River. It’s the greatest hopper fishing in the world. They swarm like bees, and the big brown trout cruise the banks waiting for them to get blown into the water. In fact, several times I’ve seen large fish jump on to the banks and flop around to knock the hoppers into the water, then they flip back into the river and eat them. You’ll often see slimy spots in the grass on the bank, where the fish have landed.”

He rolled his head back and his eyebrows went up to his hat. “You’re joking, no? Saltemontes means ‘grasshopper’ in Spanish. The Lodge is on the Ñirehuao River. It’s the greatest hopper fishing in the world. They swarm like bees, and the big brown trout cruise the banks waiting for them to get blown into the water. In fact, several times I’ve seen large fish jump on to the banks and flop around to knock the hoppers into the water, then they flip back into the river and eat them. You’ll often see slimy spots in the grass on the bank, where the fish have landed.”

Although I found the last part of his tale a bit tall, I was

in a vulnerable frame of mind, since I was trying to fish a river where at least a half-dozen tiny bugs were always hatching simultaneously and after a day of total futility I had to face the guy in the fly shop who would tell me that the only thing working was some obscure fly that, of course, was completely sold out. Hearing of a river where you could prowl the banks all day with a big bushy fly, and with fish so aggressive that you had to hide behind a bush to tie it on your line, sounded like heaven.

The next February I was off to southern Chile. After traveling for well over 20 hours my guide picked me up at the Balmaceda airport. “I assume that you didn’t get our email?”.

“No. I haven’t looked at my email in four or five days. Why?”

“Well, we’ve had a bunch of rain and the river is running a bit high. We emailed all of our guests three days ago telling them not to come. When we arrived at the lodge after driving for an hour and a half, I saw what he meant. The river, which was normally about the size of the Rivanna, was now as broad as the James, and it was an ugly chocolate brown color. “Is there any point in fishing this?”

“No, it’s a hundred-year flood. Highest that we’ve ever seen it. It won’t be fishable for at least two weeks.” If my life were measured by the number of “hundred-year floods” that I’ve encountered at lodges, I’d be older than Methusalah.

“So, what’s the program?”

“No program. You might as well leave tomorrow.” The next day I caught a flight about 500 miles north, where I discovered some excellent fishing in Chile’s beautiful Lake Country, which I have revisited three times with great pleasure. To the Lodge’s credit they gave me a free week of fishing the following year, which I thoroughly enjoyed despite more rain, though I never did see a big brown trout swatting hoppers off the bank.

But there was another night in the A-Bar that is my most memorable. I met an old angler named Whitey Whitmore who, in the past ten years had become a legend on the Ranch, fishing it exclusively and every day during the season. Supposedly, he could catch ‘em when and where no one else could. He had a grungy grayish white beard – was a spitting image of Foster Brooks – and, as it turned out, shared many oratorical flourishes with that great rhetorician. We chatted over a beer then hooked up as partners on the pool table. Our first match ended when Whitey sank the 8-ball on the break. It caused a bit of a fuss, because he broke the rack so hard that two other balls left the table. Our opponents protested, and we agreed to let the bartender rule. His sage decision was that “If someone is good enough to sink the 8-ball on the break, he shouldn’t be accountable for collateral damage.” In our next match, Whitey sank the 8-ball on the shot after his break, so we got bounced and repaired to the bar, even though I had not yet taken a shot. He switched to his regular drink, Jägermeister and Squirt, and began regaling me with stories of angling adventures in his life before he had settled in to fish the Ranch into eternity. Seems that after hearing any far-fetched or wild rumor, he would head off to the most remote corners of the world in search of exotic fish that could perhaps be caught on a fly. His final tale, though a bit garbled by booze, has remained with me and I have often lamented the fact that I have not followed its trail. I’ll pass it on as I heard it.

While fishing for eels on a river in Moldova, Whitey had met Aristotelis, a Greek angler who said he had recently returned from his best trip ever, fishing for giant prelapsarian taimen, a trout-like fish, in the remote mountainous northeastern corner of the former Soviet republic of Kojakistan. These fish live only in the Stavros river system where they have survived for thousands of years. Normally the big taimen feed only on smaller fish and aquatic newts deep in the river’s largest pools. But in late May, seed pods drop from the beech trees that line the river, some ferment on the ground, and lemmings feed on them. After eating the fermented pods, the lemmings become disoriented, and many fall off the bank into the water. The sight and sounds of the inebriated lemmings thrashing about and belching loudly catches the attention of the taimen, and they come to the surface to eat them. In fact, for a period of several weeks, their diet consists almost exclusively of besotted lemmings, and that is when they can be caught by twitching big bushy flies on the surface. Aristotelis said that the taimen were the strongest fish he had ever encountered, and that in five days he had hooked about twenty, but had landed only three, the largest being over 70 pounds. Some that he lost were much larger, exceeding 100 pounds. He claimed that his problem was that he had only moderately heavy rods that he used for salmon, which were too light. In the five days, he had broken all three of his rods and lost two fly lines to the giants.

Aristotelis’ tale caught Whitey. When he returned to the U.S., he first attempted to find someone in Kojakistan that he could contact regarding the fishing possibilities, but failed. The internet had just reached there and the national website merely said “Under construction. Please return if we finish”. He visited Kojakistan’s consulate in Washington, but the entire staff consisted of Americans of Kojaki descent from Toledo who had never actually been to the country, and knew little about it except that their grandmothers had always prepared the national dish, pickled rutabaga in fermented yak milk, for special holidays. But, being an undaunted angler, the following May, Whitey tied up some lemming flies, packed his heaviest rods and caught a Flying Yak Airlines flight from Baku to Savalas, an ancient Greek city that was founded by Alexander the Great’s food taster who deserted from the army in 327 B.C. on the way to India after eating a bad date, and which is the modern capital of Kojakistan. He checked into the Telli Hotel, the only one in Savalas with indoor plumbing and turn down service, and began to ask around for information on the Stavros River. He finally tracked down Abbimann, a local yurt-maker who spoke a bit of English because his brother was a third-degree shaman at the Kumbaya Yurt Colony in Boulder, Colorado. He offered to take Whitey to the Stavros for 500 Kopeckiz, the equivalent of $6.37. The next day they left for the river in Abbimann’s beaten up UAZ Patriot, a Russian SUV known for its massive cup holders which can hold four two-liter bottles of vodka, and usually do.

Although the Stavros was less than 100 kilometers away it took five days to get there, traveling on terrible dirt tracks. They passed only one other vehicle, a rusted out 1958 Edsel, and a few nomadic tribesmen riding yaks. When they arrived at the river in the early evening, Whitey was surprised, first at its size and then at its beauty. It was well over 200 yards wide, very clear, with huge deep pools separated by long glides. While Abbimann was setting up their yurt by a beech grove, Whitey began exploring for signs of lemmings. There were a few seed pods on the ground but no evidence that any were being eaten, or of lemmings. When he walked down to the river he noticed some tiny flies in the air and small dimples on the water. He caught one of the flies, which looked surprisingly similar to a fly that he occasionally found on the Henrys Fork. He then started examining the water. My god! The dimples were from trout, not taimen– and they were enormous. Every fish he saw was at least five pounds, some were over ten, and all were gulping the tiny flies. He couldn’t believe it. Aristotelis never mentioned the trout. He had bought only four very heavy rods and lines, huge flies, and materials to tie more of the same, and he was camped in dry fly nirvana!

But Whitey had come to catch the giants, so he remained calm, suspecting that lemmings probably ate the pods during the night and then, in their stupors, fell into the river in the early morning. He turned in early to listen for the familiar soft crunching noise made by a munching lemming, followed shortly thereafter by the high-pitched squeal of ecstasy that comes with intoxication. It never happened. When he arose in the morning, he heard only one sound – slurping fish. By 9 A.M. the air was already full of small mayflies and the huge trout were gorging on them. Whitey was helpless with his heavy rods and lines, and no small flies. But he couldn’t give up. He strung up his lightest rod, put on his smallest lemming imitation, and started casting. All he succeeded in doing was scaring the trout.

Although Abbimann didn’t fully understand Whitey’s problem, he had the solution. “We can get the big fish up with explosives. I’m sure we can buy some in the village downriver. The natives here make it from yak dung.”

“Really, yaks produce good fertilizer for making bombs?”

“Most powerful stuff you can get. If you’d ever walked behind a yak all day, you’d understand”.

Whitey didn’t even try to explain the problems with using bombs, but sent Abbimann to the village to get information on the lemming/taimen situation. When he returned that evening the news was not good. The lemmings run in cycles – three years of proliferation and three years of disappearance. Last year was the end of a cycle of proliferation. This year there are very few lemmings and the taimen are sulking at the bottom of the deepest pools. Nothing will bring them up but explosives.

That evening Whitey watched the largest brown trout that he had ever seen – he estimated it at over 15 pounds – sucking in the small flies. He spent the next day casting lemming and chipmunk imitations through the pools without ever moving a fish, while all around him monster trout were feeding voraciously on small flies. Never had fishing made him so depressed. Why hadn’t he packed just one light weight rod and line and a few small flies? Why did he let his planning for this trip be dictated by one goofy Greek. He cursed Aristotelis a hundred times – another Greek gift gone awry.

A second day of futility and Whitey was finished. Seeing rising trout everywhere and having no way to fish for them was too much to endure. The next morning Abbimann packed up camp and they left for the long drive to Savalas. Eight days later he arrived back in the U.S. Although he planned to return to Kojakistan with more versatile equipment, the brutal coup six months later led by the President’s mother-in-law, and the installation of the repressive and paranoiac dictatorship under her bastard son, the enigmatic Danfra Zer, who immediately banned sport fishing and sky diving, quashed those plans. Shortly after, Whitey gave up his Gadabout Gaddis life, and retired to Last Chance to spend his remaining years chasing trout that were rarely as large as the smallest he had seen in Kojakistan, hanging out at the A-Bar and spinning his yarns.

By the time Whitey finished his story he was sloshing his words, making Foster Brooks look like temperance. I wanted to be sympathetic. “God, what a depressing story! You had a shot at maybe the greatest dry fly fishing in the world, and came up empty. How’d you get over it?”

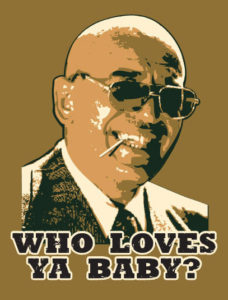

“I dint. Neber haf.” At that moment, a stout bald man with a tootsie pop hanging from his mouth and wearing a tee shirt with the message “Who loves ya baby?” approached Whitey and threw his arm around him. He looked at me. “Whitey feeding you full of his ridiculous fishing stories?”

Whitey looked dazed but responded. “Deh’r all true. I’d neber lie about fishin.” At that moment he eructed, slipped off the stool and went to the floor. I jumped down to check on his condition but the bald guy had already hoisted him over his shoulder and was heading toward the door. Whitey protested. “I gotta finish my story. Why you taking me out? You sonabitch Greek.” But the bald guy and Whitey were out the door.

So, I was left to contemplate Kojakistan, and its monster taimen and trout. I don’t know if Whitey outlived the A-Bar, but I miss them both.