Christmas is drawing nigh, the weather has changed, and the seemingly endless election is over – or is it? In the time of Covid, uncertainty stalks the land. Will a vaccine really work? Or maybe three or four? Will we have a choice, and how would we know which to choose? In this age of fake news and rampant conspiracies, will enough people agree to take a vaccine to create herd immunity, or will we still be masking next summer? We’re in Rummy’s world of known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. My personal known unknown is that I will probably not be going to Argentina to fish in 2021, for only the third time in over two decades, since Covid has closed the country indefinitely for American visitors.

My first trip to Argentina was in January, 1995, with my son Tom, then a college senior. After spending a few days sightseeing in Buenos Aires, we flew about 1,000 miles southwest to San Carlos de Bariloche, the largest city in Argentine Patagonia. Brock Richardson, our guide for the trip, met us at the airport with his van. Bariloche is situated on the large and beautiful Lago Nahuel Huapi, surrounded by snow-capped mountains. By the way, the names of the lakes, rivers and many other features in Patagonian Argentina, are not Spanish, but from the spoken languages used by the region’s indigenous tribes. We by-passed the City and Lake, to head a couple of hours north for a two day stay at the Primavera Lodge on the famous Rio Traful, which runs from Lago Traful for about 10 miles into a reservoir.

The Traful is known for its lovely turquoise pools, fascinating rock formations, enormous trout, and landlocked salmon, the latter a rarity in Patagonian rivers. Our Lodge and its entire side of the river was acquired by American magnate, Ted Turner, in 1998, and is now off limits to everyone except for himself and his guests, which angers many Argentines, who consider the River a national treasure. The other side of the River is owned by an Argentine family that operates one of the more luxurious and expensive fishing lodges in the world. There is a hatchery on the Traful, and some of the best fishing is just downstream from it, as the hatchery food leaks into the River, and the fish eat constantly with minimal effort, often becoming obese, much like a dump bear. We caught some very nice trout of over 4-pounds throughout the river, but in the hatchery section Tom hooked a real monster. The fish rocketed up from the bottom and attempted a jump, that I suppose it remembered being able to do in its youth, but in its now-corpulent state, it failed and as its tail was about to clear the water, it collapsed and fell on the leader, breaking it. The fish of a lifetime, but we had to laugh. We guessed that it was nearly two-and-a-half feet long, and weighed well over than ten pounds. Later, at the Lodge, we examined the logbook and found numerous entries in past decades describing trout that were of similar bulk. During that first stay, we were introduced to the wonderful Argentine flan, served with dulce de leche, the delectable caramel-like sweet sauce – made from slow-cooking cow’s milk and sugar – which Argentines eat on many foods, and is now popular in the U.S. The combination remains a favorite of mine.

We left the Traful and drove several hours northeast to the fabled Chimehuin River, which drains from Lago Huechulaufquen, near the Chilean border, and runs about forty miles before joining the Aluminé River. Our first encounter with the Chimehuin went badly. The wind was blowing a gale, even on Patagonia’s lofty standards, and there were few bushes or trees lining the banks to block it. Casting a dry fly with our light rods in such a powerful wind was hopeless, so we fished under the surface with weight and short lines. As we were standing in the current, the raging wind literally blew us upstream. And because it was swirling, even fishing a short line was difficult and risky to our body parts. It was most unpleasant and after a couple of hours of catching nothing, Brock decided that we would move to a section of the River that had better wind protection.

Just after pulling out of the field where we were parked, traveling on the rough dirt road heading toward the main paved road, we picked up an Argentine soldier hitchhiking back to his base, which Brock said was about 20 miles away. Brock spoke only a little Spanish and Tom & I even less, so we couldn’t ask him how and why he got there. Minutes after picking him up, the van sputtered a couple of times, then died. The soldier immediately got out and started walking up the road, wisely escaping his ride from hell. Brock got under the van and came back with the bad news – a broken accelerator cable. Then we noticed that several hundred yards up the road the soldier leaned over, picked up something, turned around and was walking back toward us. When he reached the van, he showed us what he had found – a wire hanger. Brock immediately got it, saying “that’s our cable.” Amazingly, it seemed that our guest must have quickly diagnosed the problem and, like any good soldier, he marched off to find a solution. We couldn’t determine which of the events that we had witnessed was the most bizarre – that a soldier was hitchhiking on a remote dirt road leading to nowhere but a dead end, that there was a wire hanger lying along that same road, or that the soldier found the hanger and knew that it was what we needed. In any event, we felt partially blessed, then fully after Brock added to our wonderment, by crafting a working cable from the hanger, and attaching it. The van coughed a bit, and wouldn’t go very fast, but we were on our way again.

Brock rightly decided to drive the soldier back to his base, and used his satellite phone to call a local friend, Hector Scagnetti, and ask him to come meet us. He arrived, left his car for us to continue fishing, and drove the sputtering van the hour or so back to his home in San Martin. We had a mediocre afternoon on a slightly less windy stretch of the River. Brock mentioned that Hector and his wife Ida owned Cabañas Arco Iris, a group of five lovely small houses on their property, which they rent to tourists, and that Hector had asked him if the three of us would like to join his family for dinner at their house, close to our hosteria (small hotel). We jumped at the chance. When we arrived at their house, Hector and Ida met us, accompanied by their two children, Mariana, a senior in high school, and her two-year younger brother, Ezequiel. Hector was standing by our van, and said something in Spanish to Brock, the only bit that I could understand being the words “Americanos” and “jury-rig”. I asked Brock what he had said, and he wasn’t exactly certain, but thought it translated roughly as “You Americans don’t know how to jury-rig anything”. I was surprised that someone who spoke very little English would know the odd expression “jury-rig”, but many subsequent experiences in Argentina have enlightened me as to its importance. In a couple of hours, Hector had taken the same hanger and built a “proper” cable. It worked perfectly for the remainder of our trip, and two years later Brock told me it was still on the van and doing fine.

Dinner with the Scagnetti family was delightful. Ida served a superb Italian-Spanish fusion meal, and Hector’s local wines were excellent. Mariana, had studied English and was fluent. Her parents and brother spoke only a few words of English, so Mariana interpreted for all of us. She was smart, self-confident, attractive and funny – very impressive. At a point in the engaging evening, I asked her whether she was going to university. She said that her family could not afford it, and she hoped to get a job in the travel industry, as San Martin was a popular tourist destination. I suggested that, given her command of English and obvious intelligence, perhaps she could get a scholarship to attend an American college. When Mariana explained to Hector what I said, he nearly choked on his food. He was not happy, no doubt wondering why this American stranger would plant the thought with his beloved daughter of leaving home to attend school abroad, and how the family could ever afford the cost of such a venture. But the seed germinated, and it serendipitously led all of us on an unexpected and wonderful relationship that has lasted for over 25 years. When I returned home, I checked with several colleges in the Northeast and found that Mariana would need to take the International SATs to be considered for admission, which was impossible for her. But Brock contacted Westminster College, an excellent small school near his home in Salt Lake City, and it did not require the exams. So, Mariana went there with generous support from the Richardson family, graduated in three years while working several jobs, married a Utahn, and has built an impressive career in finance. She became head of Latin American client services for a large Western bank, and is now running her own private wealth management business in Salt Lake City, that serves many prominent Latin American business owners and their families. A real American immigrant success-story.

After our dinner, which ended at nearly midnight, Brock asked Tom if he’d like to go to the local disco. I told them it was okay with me, but we were gathering for breakfast at 8AM, regardless of how little sleep they got or how hung-over they were. They staggered in about 7AM. Tom said that there were only a few people in the disco until after 2AM, then a huge crowd showed up, and he and Brock were among the first to leave. This story seemed far-fetched, but gained credibility, when we noted as we left our hosteria about 9AM, that two young men who were employed behind the desk, were just arriving for work, directly from the same disco. Brock and Tom had a rough day, but to their credit, we lost no fishing time.

After the night in San Martin, we traveled nearly 100 miles north, mostly on dirt roads, with excellent fishing in three other fine rivers, before returning to Bariloche to fly home. It was a great trip, and I was eager to return. Two years later I did. I bought a few maps to do some planning, and decided that I could rent a car and find access to the rivers that we had fished, and perhaps others, without use of a guide. I have always preferred to fish alone or with a friend. I faxed Hector to see if he would like to fish with me for a few days, assuming that he could get my message translated. He responded that he would, and even invited me to stay at their house.

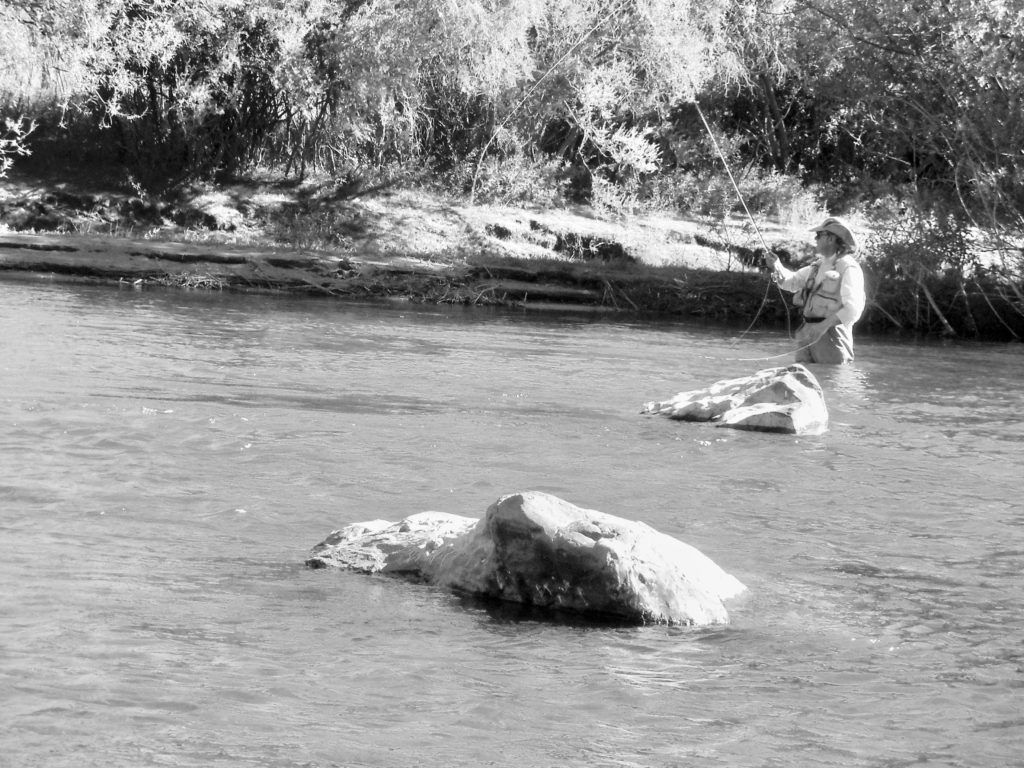

In early February, 1997, I traveled to San Martin. I had identified a spot on the drive from Bariloche where the road crossed the Quilquihue River, and it looked to be about a one mile walk down to its confluence with the Chimehuin. The Quilquihue was too deep and closed in by willows to walk in, there was no obvious trail, and it took far longer to bushwhack through the trees and the damnable briars than I expected. When I got to the Chimehuin, I was at the head of a long, deep pool, lined on my side with large willows. A beautiful riffle entered the pool over a gravel bar. As lovely a spot as I could imagine. But to fish the pool I had to wade across the river, which was over 20 yards wide, up to waist deep and moving fast. I made it, but not without considerable trepidation. The wind was blowing hard. At the top of the pool, on the far side under a big willow, and barely within my casting range, was an eddy – a typical spot for fish to be feeding. I put on a big dry fly and cast it into the eddy, where it immediately began to drag unrealistically. Damn! Then bam! A large trout hit it, jumped several times, and eventually I landed the 19” rainbow. A few minutes later I caught a clone of that fish in the same spot with the same ersatz technique. As I moved downstream, fishing across the pool to the willows on the far side, no fish moved. At some point, I lazily let my line drift until it was straight downstream, and as I raised my rod and began stripping it in, it was eaten by a large brown trout, which I soon netted. It suddenly dawned on me that these fish wanted floating flies being pulled upstream. The rest of the day that’s how I fished through the big pool and two below it that were similar. It was one of the best days of fishing that I have had, with about 30 fish from 15”-20” coming to the net, using a strange technique, and despite the relentless wind.

I was a bit anxious as I drove to Hector’s house, as we had met previously only for a few hours and hardly spoken at all. But when he greeted me with a warm welcome, speaking English, I completely relaxed. I had a wonderful dinner and evening with him, Ida and Ezequiel (Mariana was in College in the U.S.), exchanging information about our lives and families, and of course I told him about my exceptional day of fishing. He had never been to the spot and wanted to go there the next day, which we did, finding a much better route for walking. Of course, it was like a different river. The wind had subsided, the fish wouldn’t touch a fly that was swimming upstream, and we each caught six or eight – not bad but far short of my solitary experience just one day earlier. We fished together on another famous river, the Malleo, for two more days, then I went farther north to fish by myself for five days, before returning to San Martin, then home.

Fishing with Hector introduced me to mate (pronounced matay), an herbal tea made from leaves of the yerba mate plant, which contains caffeine and a second mild stimulant. Nearly everyone who I’ve met in Argentina drinks mate, often throughout the day. Typically, a small ornamental cup is about half-filled with ground leaves, and hot water is added. A silver straw is used to drink the mate, serving as a filter to block leaf particles from being in the drink. Mate is quite bitter, and I find it difficult to digest. It’s ritualistic, a bit like smoking pot fifty years ago. When a cup of mate is prepared, it is often passed around to whoever is present, and guests are traditionally offered the first drink, which is supposed to be the purest and best. Hector would drink mate with breakfast, for twenty minutes or so before he would begin fishing, then take a mate break during the day, and often have cup when we arrived back at the car. Usually, mate was accompanied by a cigarette. While he was drinking, I was often fishing, yet he generally caught as many fish as I did. Perhaps a bit more contemplation on my part would enhance my success.

While staying with Hector and Ida, I have gotten to know San Martin. With a population of about 25,000, but many more in the summer, it is the nicest town that I have visited in all of South America, and for me, the equal of any in our Rockies. It has a gorgeous setting, next to the beautiful Lago Lacar, surrounded by high mountains, and has a fine ski area, public beach. excellent restaurants, hotels, shops and a myriad of summer outdoor activities, such as hiking, fishing, camping and golf. It is very clean, and looks Tyrolean, with many half-timbered houses and finely crafted wooden buildings. And, apparently, a thriving disco.

In subsequent visits to Argentina, I have fished in dozens of rivers extending over a region running from 300 miles south of San Martin to 100 miles north. On several trips Ann has joined me, not only for fishing, but to visit sites such as the spectacular Iguazu Falls, Mendoza and its wine country, and the excellent beaches in nearby Uruguay and Brazil.

But, even more rewarding than the great fishing and sightseeing, has been the warm friendship that Ann and I developed with Hector and Ida. We have joined them in Salt Lake City, Paris, Washington D.C, and our homes in New York and Virginia. We have also visited Mariana in Utah and New York, and Ezequiel, when he lived for several years in Belgium. And, it all started because of a broken accelerator cable.

Tragically, Ida passed away three years ago, and we miss her terribly, but we have enjoyed meeting the charming Monica, who Hector knew in high school, and recently reconnected with through Facebook. Those trips, and my subsequent fishing excursions in Argentina, have provided fodder for future articles, that I hope to write.