Since moving to Keswick eight years ago, I have learned to enjoy fishing in our two ponds and some of those on our neighbors’ farms. Catching a large bass or catfish, or even a good brim, on a fly rod is exciting. But, the allure of traveling to far-flung locations to experience the joys of fly fishing while immersed in an entirely different culture continues to be addictive.

Since moving to Keswick eight years ago, I have learned to enjoy fishing in our two ponds and some of those on our neighbors’ farms. Catching a large bass or catfish, or even a good brim, on a fly rod is exciting. But, the allure of traveling to far-flung locations to experience the joys of fly fishing while immersed in an entirely different culture continues to be addictive.

On a clear day, the flight from Katmandu, Nepal to Paro, Bhutan provides a spectacular view as you soar only a few thousand feet above eight of the ten highest peaks in the world, including Mt. Everest. It is a perfect introduction to a beautiful and captivating country. On the way from the airport to the hotel, Ann and I were dropped off in a small village for a few minutes while our guide, Tshering, a former monk, and our driver, Gyaling, ran an errand. As we were about to enter a shop, a friendly looking young man dressed in the traditional gho (i.e., robe) approached us, offering me his hand. I shook it. He greeted me politely. “Hello sir. How are you?”

“I’m fine sir. How do you like Bhutan?”

“We have just arrived, but I think that we will like it very much”

“How long will you be here, sir?”

“Ten days.” I now opted to add a little substance. “I’m going to fish in some of your rivers.”

“Sir, this is a Buddhist country. Fishing is against our laws. It is sinful to harm any living creature.”

Ann smiled wryly, thinking perhaps that given my angling skills there was little chance that any religious tenets would be violated. But I was worried, since fishing was the main reason that I had come to Bhutan. At that moment, our car pulled up, and I was rescued from further embarrassment. Looked to our guide for reassurance. “Tshering, that young man said that fishing is not permitted in Bhutan. Is that true?”

Ann smiled wryly, thinking perhaps that given my angling skills there was little chance that any religious tenets would be violated. But I was worried, since fishing was the main reason that I had come to Bhutan. At that moment, our car pulled up, and I was rescued from further embarrassment. Looked to our guide for reassurance. “Tshering, that young man said that fishing is not permitted in Bhutan. Is that true?”

Tshering didn’t hesitate. “Yes. We are Buddhists and cannot fish. But you have special permission from the Royal Family, so it will be okay for you.” After traveling such a long distance, what a relief. And it all worked out. I fished on four different rivers, catching trout on all of them. The rivers were as beautiful as any that I have fished elsewhere. And no other anglers crossed our path. But, there is much more to Bhutan than fishing.

Bhutan is a small country, about one-third the size of Virginia. Though largely agrarian, it is quite prosperous, and the traveler sees none of the abject poverty that is common throughout India and China. It is also geographically diverse. In the north are the high Himalayas, with peaks of nearly 25,000 feet, and in the south, only 80 miles away, the elevation drops to 500 feet. Northern fauna includes mountain sheep, snow leopards, wolves and the national animal, a supersized goat called the takin. In the subtropical forests of the south are elephants, tigers, water buffalo and cobras. We saw huge macaques near the road in the mountain passes at over 10,000 feet. The human population is under 750,000, about half of whom live at least a day’s walk from any road, including many more than several days. Thimpu, the modern capital, is by far the largest city with a population of about 80,000. From 1907 until 2008, Bhutan was ruled solely by the Wangchuck dynasty, but in 2008 the 53-year old King voluntary abdicated his throne, changed the political system to a constitutional monarchy, with a bicameral legislature, and named his son as the new King with greatly reduced powers. Perhaps no country ever had a more seamless transition to democracy. Every Bhutanese with whom we spoke expressed love and admiration for the current king and his father.

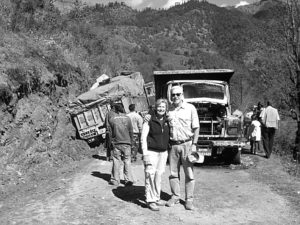

All flights to Bhutan land in Paro, in the western end of the country. Tshering told us that it was the only location in the country where a straight, level runway long enough to handle large planes could be built. We never saw another spot that would meet that test. A single road heads east from Paro, eventually ending before the Indian border, and three roads turn off the east-west road going south into India. There are a couple of dirt roads that go north for a short distance, but none pass through to China or even reach the high peaks. Although the primary roads are mostly paved, they are all steep and narrow with frequent huge potholes and constant switchbacks. Average driving speed is about 15-20 miles per hour, but driving never was tedious because of the beautiful and beguiling scenery.

Many surmise that Bhutan was the model for the mystical paradise, “Shangri-la”, in James Hilton’s popular 1933 novel Lost Horizons, perhaps because it was a completely closed country until the early 1970s. No foreigner could enter Bhutan unless invited by the Royal Family. So the rest of the world had virtually no information about the country, inspiring leaps of imagination. In the 1970s, the King noted the demise of all of the other small Himalayan kingdoms (e.g., Tibet, Sikkim, Mustang, Ladakh) that were sandwiched between the two aggressive powers – India and China – and decided that if Bhutan were to remain independent, Western visitors had to be invited in to see the idyllic countryside and meet its charming inhabitants. He also changed the educational system to require teaching in English (the Country has eight languages), so locals could communicate with the new visitors. Tourism is still in its infancy, with just over 100,000 total tourists estimated for all of 2015, about 10% of which were Americans. All visitors must use a Bhutanese tourist agency (they have U.S. affiliates) and travel by bus, or by private car with a driver and guide. No independent travel is permitted. Your first day on the roads will convince you that you don’t want your guide to also be driving.

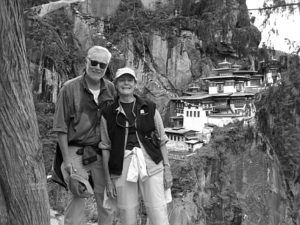

Buddhism is the state religion of Bhutan, and evidence of the depth of the peoples’ commitment is palpable. All government administrative buildings (called “Dzongs”) contain a temple, and religious buildings and religious monuments dot the landscape. Plots of prayer flags are ubiquitous, and monasteries are visible on many mountain tops, including the famed “Tiger’s Nest”, one of the world’s great sights. Bhutan has many of the highest unclimbed peaks in the world, as they are considered sacred and climbing them is prohibited. Both polygamy and polyandry are permitted, though rarely practiced by ordinary citizens. But the former king has four wives – all sisters from a family of six girls. In Bhutanese villages, many houses have paintings on the outside walls, with perhaps the most common theme being a giant phallus. Sex education is not a controversial topic.

Fishing in Bhutan is for brown trout, except in the far south, where the giant and elusive mahseer can be found in warmer rivers. The trout were brought from Kashmir, where they were originally introduced by the English in the 19th Century, as were the trout now residing in many Asian and African countries.

The first two rivers that I fished were the Paro Chhu (the local word for “River”) and the Mo Chhu. These were both classic trout streams, broad and clear, with long riffles and deep runs, but with no visible insect activity or rising trout. The banks were lined with rice fields and virgin forest. In the Paro I caught a half dozen fish up to about 12 inches, but in the Mo only a single small fish. I couldn’t get any fish to come to a dry fly, but caught them on standard nymphs. I would love to give the Mo another go, as Tshering said that it was unique in having large trout of up to 10-12 pounds.

Although Tshering was not a fishing guide, he had accompanied a few other anglers in the past, and it quickly became apparent that he had developed an interest in angling that was beyond “passive”. He set up a rod and tied on a fly, ostensibly for me in case I managed to break or lose mine, but several times when I looked toward him I noticed that his line had inadvertently fallen on the water, and was floating downstream in a manner that could easily, though of course accidentally, hook a fish. Supposing that I should not bear witness to such un-zenlike activity, I kept my counsel.

On our drive back to the small hotel in Punakha after fishing the Mo, Tshering said that the hotel restaurant had some “special hot chiles”. Although there is variety in Bhutanese food, the staple is rice and chiles. Both Tshering and Gyaling ate rice and chiles for breakfast, lunch and dinner every day. Large numbers of chile peppers were drying on rooftops or hanging by windows on many homes. We had sampled the “regular chiles” and found that even a small bite was incendiary and would require a bottle of beer for relief. The thought of special hot chiles terrified us.

Later, at dinner, the waiter placed a small bowl of round orange chiles in front of Tshering. He offered one to us. We respectfully declined. He popped one into his mouth. Immediately, his eyes bulged and teared, and he began choking. He tried to speak, but nothing came out but short gasps of air. He then began sweating profusely, and his shaved head and the shirt under his gho were soon completely drenched. He stood up, turned to leave the table, but couldn’t speak to tell us what was wrong or where he was going. He disappeared through a swinging door which led to both the bathroom and the kitchen. Ann looked at me and said “I feel bad for him, but I don’t know what we should do”. I responded with my usual empathy. “I think this has happened to him before”. About ten minutes later he returned, still looking stressed. His words were a bit slurred, but we believe that he said “These are really good chiles”, as he popped another into his mouth. It was our longest dinner in Bhutan.

The farthest east that we traveled was in the Bumthang Valley, about 100 miles from Paro. From there, one morning, we drove for two hours on a rough dirt road through a beautiful valley, to fish the Tang Chhu. I entered the lovely, crystal clear stream near a large plot of Buddhist prayer flags, and upstream from a narrow suspension footbridge. I had just begun casting, when Ann signaled me to turn around. On the bridge about a dozen children had gathered to observe my strange behavior. After ten minutes or so, I hooked and landed a small fish. They applauded, and immediately I felt a great weight lifted from my shoulders. Fortunately, Tshering relieved the pressure by taking me upstream to a deep pool sequestered in the shadow of a high cliff.

The new pool proved to be full of fish. I hooked one on almost every other cast by drifting a small nymph downstream, and slowly stripping it back. The brown trout in the Tang had unusual coloring, the sides being gray, with many brilliant red spots. The largest I caught was just over a foot long, but they were feisty, and are etched in my memory. After an hour or so in the pool, some clouds drifted overhead, blocking the sun, which triggered a hatch of small mayflies with gray wings. Fish rose regularly in the foam to take the flies. I tried all of my small dry flies that looked like the naturals without success so, as is often the case, I still have no idea what was going on.

We left the Bumthang Valley, returning west, then turned south on a road extending about 15 miles into the Probjikha Valley. This valley is the winter home of the black-necked crane, a sacred (and endangered) bird that migrates annually from Tibet to this and only one other valley in Asia. The people living there have chosen not to have electricity, because they are afraid that overhead wires will upset the cranes, causing them to opt to winter elsewhere. Sacrifices are the daily bread of these devout Buddhists. We saw several of the impressive cranes that had only recently arrived.

The Probjikha Valley also is home to a pristine creek emanating from a mountain spring. While Ann visited a local elementary school which, because of deference to the cranes, had no lights or heat, Tshering took me to the creek. Like many spring creeks, it meandered for many miles through a flat valley. It was perfect dry fly water, but I did not see an insect or a fish rise. In one long, deep pool I caught many small fish on a dry fly but in the other mile or so of the stream that I walked, none rose to a dry fly, even under the cut banks. I was able to catch some fish on nymphs, but I left this lovely stretch of water with a slight sense of disappointment. At one point, Tshering wandered off with my spare rod and was caught fishing by a local, who chastised him very aggressively for his sinful behavior.

On the drive through Bhutan, we passed four or five other beautiful rivers, and Tshering said that all of them have trout. The few reports on Bhutan fishing that I have read by other anglers have extolled the beauty of the rivers, but noted the dearth of larger fish. Some have surmised that the factors causing this could be high elevation (although many of our Western rivers are at similar elevations of 5,000-8,000 feet) or a paucity of insect life. Frankly, I don’t have a clue. But I do know that if you like standing in beautiful rivers, gazing at snow-capped peaks, meeting and talking with enchanting children along the river bank, while also experiencing a unique and fascinating culture, it would be hard to beat Bhutan.