The Coronavirus lockdown is in its eleventh week. Recently I read an opinion piece asserting that we should charge reparations to China for creating the virus and exporting it to our shores. It made me wonder if Spain paid reparations for creating the worst pandemic of modern times – the Spanish Flu of 1918, which killed between 20 million and 50 million people worldwide, depending on whose statistics you believe. So, being flush with time, I decided to do a little research.

The first entry on Google was from the History Channel, a seemingly dependable source. This is the story:

The most likely origin of the 1918 flu pandemic was a bird or farm animal in the American Midwest. The virus may have traveled among other animals, then mutated into a version that took hold in the human population. The best evidence suggests that the flu spread slowly through the U.S. in the first half of the year (the first known case was reported in early March at a military base in Kansas), then spread to Europe via some of the 200,000 American troops who traveled there (in March and April, 1918) to fight in World War I. By June, the flu had mostly disappeared from North America, after taking a considerable toll. One of its first stops abroad was in Spain, where it killed so many people that it became known the world over as the Spanish Flu, although the Spanish believed the virus had come from France, so they called it the “French Flu.”.

Based on this account, not only did the 1918 Flu start in the U.S., but we let Spain, a major victim, take the blame for it. COVID-19 has a similar history –starting in China, but with the U.S., thus far, suffering the greatest damage. Under the standards of 1918, it would be called the “American Virus”. But, the rest of the 1918 story is even worse. After virtually disappearing, the Flu came back with a vengeance in September (the “second wave”), and between then and the end of the year over 600,000 people died from it in the U.S. (when our population was 30% of today’s), and tens of millions worldwide. By early 1919, without a vaccine, the Flu had again virtually disappeared. I know that COVID-19 is not a flu, but given the history of 1918, I sure hope that it knows it.

Historians and journalists love to draw insights from historical comparisons, and many have written that the American public’s behavior in the aftermath of COVD-19 may mirror it following the 9-11 attacks. That makes no sense to me, as one is a discrete incident, fortunately not followed by subsequent incidents, and the other is a continuing pandemic. But reading the analogies got me thinking about the 9-11 attacks, and how I remember them. For us older folks, the attacks are notable, perhaps along with President Kennedy’s assassination, in that most of us can remember precisely where we were and what we were doing when the horrific events took place. For 9-11, I was in Mongolia.

Mongolia, a country about the size of Alaska, with only 3 million people, is on the bucket list of many fly fisherman who enjoy traveling to exotic destinations. Getting there is a haul. On September 9, 2001, I flew from New York to Chicago, over the North Pole to Beijing, then on to Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbataar, I planned three nights there – to look around – before a 4-hour helicopter ride to the fishing camp in the north, close to the Russian border. An odd thing happened when I was passing through security for my flight from Beijing. A Chinese security guard pulled me aside, asked me to follow him into a private room, then confronted me with a serious folding knife that he had removed from my backpack. I remembered that, as I was leaving my home, I saw the knife and cavalierly threw it in my backpack, thinking that I might need it to ward off a wild animal or an attacking fish. When I passed through security in Chicago, no one had noticed it. But, in Beijing, it was a big deal. I finally convinced the security guard that I was not a threat, and he confiscated the knife, telling me that I could retrieve it when I passed through the airport again on my way home. Yeah, fat chance! But the incident may have been a harbinger – though I didn’t consider it then.

I arrived in Ulaanbataar and checked into my hotel, one of a few modern ones in the City. The next day I spent walking around the City, visiting a museum and prominent Buddhist sites. Most Mongolians are Buddhists or non-religious (a vestige of the Communist days). That night I met two other American anglers – a father and son – who would be joining me at the fishing camp. They had been visiting a tourist camp in the Gobi Desert for five days and had a fascinating story. On their second day, former President Jimmy Carter arrived at the camp. It was his first trip to Mongolia, and there would be many others, as he became a fan and leading advocate for the Country. On the third day, billionaire George Soros arrived. They said that he had never met Carter, but the two immediately became fast friends. Of course, Soros subsequently became a major supporter of the Democratic Party and its policies, and the favorite piñata of the American Right. Who knew that it all started in the remote Mongolian desert?

We had dinner in the hotel restaurant, then moved to the bar to shoot some pool. There was a television in the corner tuned to CNN. A bit before 9PM (Mongolia is 12 hours ahead of New York), a flash news announcement said that what was believed to be a small private plane had accidently flown in to the North Tower of the World Trade Center. About twenty minutes later, the second plane hit the South Tower, and it became clear that these were no small planes or accidents, and all hell broke loose. Needless to say, we were glued to the TV until late that night and throughout the entire next day, skipping our planned tourist activities. When I heard that the hijackers had used box cutters as weapons, I thought how ironic it was that the security agents in Chicago had overlooked my knife, which was a much more dangerous weapon than a boxcutter, but the agents in Beijing had considered it a serious security threat. Was that a one-off, or was it a sign that we were courting disaster? Surprisingly, the Hotel had internet service (remember, this was 2001 in one of the world’s most remote countries), and I was able to contact my wife, Ann. She was supposed to fly to Beijing to meet me after I returned there from fishing, for an extensive tour of China, but all flights were shut down indefinitely, and also she was in no mood to leave the carnage and despair in New York City, so our Chinese trip plans were kaput. I would return home as soon as I could.

The second day after the attack, we were scheduled to take our long helicopter flight to the fishing camp. We learned that we could not fly home for at least a week and probably longer, and decided that we might as well go fishing. Looking back, since I was so far from New York, in such a completely different environment, it’s clear that the emotional impact of the event was less than it would have been had I experienced it at home. That realization hit me, when I eventually returned, and I saw how melancholy, yet resilient, Ann and our many New York friends were regarding the tragedy and its aftermath.

The camp was in a beautiful narrow river valley lined with forests of pines and hardwoods, but away from the valley, nearly treeless steppes extended for hundreds of miles. There were four of us staying there, plus two American guides and a small staff. It was built and operated by a company owned by the three Vermillion brothers from Montana, who had come to Mongolia about a decade previously to check out the fishing. They obviously liked it. The camp was adjacent to a small settlement of nomads (most Mongolians outside of the capital city are nomads), who were at their summer quarters with many sheep, goats and horses. We stayed in two spacious and comfortable gers – hide-covered movable dwellings prevalent throughout rural Mongolia, often called “yurts” elsewhere. A large elevated barrel of water was heated by a fire each afternoon, to provide showers. There was a cabin where we ate our meals and could sit around to have drinks and socialize. Meat, typically mutton or goat, was served every night, usually with vegetables and fried dumplings or noodles. The beer was Mongolian, the wines were Australian, and Mongolian vodka was always available. The nomadic peoples also drink prodigious quantities of a homemade alcoholic drink called airag, made from fermented mare’s or donkey’s milk, which we sampled but never fully adopted. Mongolia is one of the coldest countries on earth, and the mid-September daytime high temperatures were 55-60 degrees (always sunny) and the nighttime lows 25-30 degrees. There was a wood stove in the center of the ger, and an attendant came by just before dawn to start a fire so we could wake to a warm ger. The air in Mongolia is pristine, and never have I seen stars as clearly as those that appeared in the night sky, compensating me for the need to step outside to relieve myself in the sub-freezing temperatures.

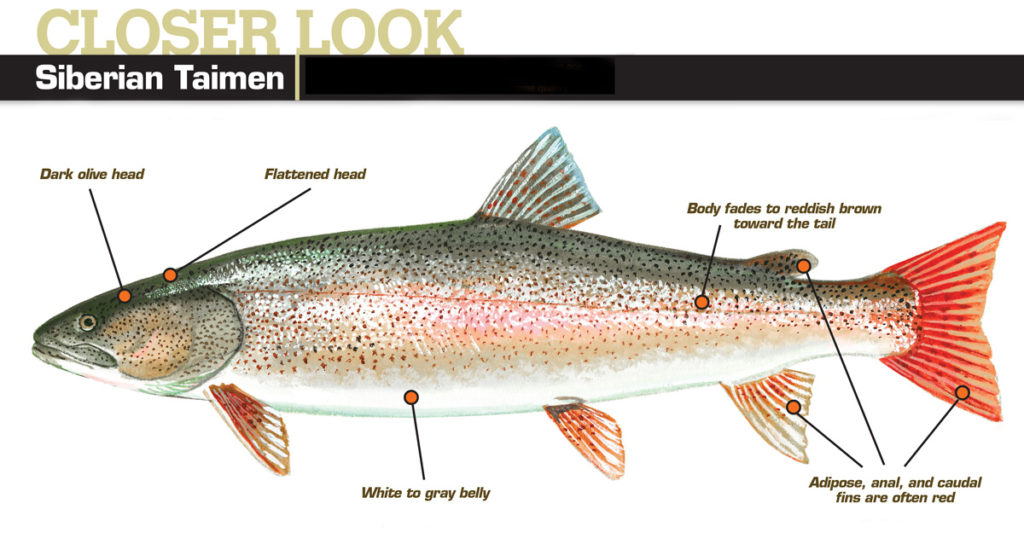

The river that the camp overlooks is large, 40-50 yards across. The fish we were after is called a taimen. It lives in the rivers and lakes of Mongolia and Eastern Russia, particularly in the rivers that flow into Lake Baikal in Russia, which is, if measured by volume, by far the largest fresh water lake in the world – a mile deep in places and estimated to hold 20% of the world’s fresh water. Most of the Russian rivers flowing into the lake have been cleaned out of taimen, but the fact that most Mongolians have no interest in eating them has saved their fish. Oddly, the only other place that taimen exist is in Europe, primarily in the Danube River drainage system, where they are called huchen. A taimen looks like a brown trout, and is genetically similar, but grows much larger. A typical example is 10-20 pounds, fish of twice that size are not rare, and examples of well over 50 pounds have been caught. Even in a big river, fish that large need a lot of territory to hunt, and are very spread out. So, the camp used jet boats that could cover many miles of river in a day. It’s impressive that such expensive boats and engines (including several extras for emergencies) had been transported from the U.S. to such a remote location. Another fish that was available in the rivers was the lenok, which looked and behaved much like a rainbow trout, and could weigh up to five pounds. But, like all anglers traveling to Mongolia, we sought the fish that eats the lenok.

Taimen, like trout, will feed on small fish and other creatures that live on the river bottom, but also will come to the surface to eat almost anything that might be swimming there, such as a mouse, lemming or duckling. Anglers can fish deep for them with streamers, or on the surface with big hairy floating flies. I chose floaters –lemming patterns about five inches long – because a taimen attacks the fly ferociously, creating great excitement. They are the absolute rulers of their domains, and if they miss a fly, they will continue to attack it all the way to the boat. There were days that I had as many as eight strikes, and one day had none. But the constant anticipation that, at any moment, a huge fish might attack my fly, was exhilarating. We fished with heavy salt-water weight rods, and casting a large bulky fly all day, with a lot of wind resistance, was tiring. At the end of the week, two of us who had fished exclusively with dry flies, had casting hands that were very crimped from holding the rod so tight in order to push it through the wind. The largest taimen that I landed was about 25 pounds, and the largest in the camp that week was about 40 pounds.

Each day on the river we would occasionally see men hanging out along the bank. The Mongolians are great horsemen, and will ride across deep rivers, but our river was too deep, even for them. Sometimes they would wave to us to take them across, and invariably our guide would accommodate them. Since we had the only two boats on about 60 miles of the river, and there were no bridges, we wondered how they ever got back. Apparently, they didn’t share our concerns. One morning, a few days after the 9-11 attacks, we saw three men listening to a short-wave radio. They motioned to us, and we pulled up to take them across. They were very drunk. Of course, we couldn’t speak to them, or they to us. About midway across, one of them grinned at us and blurted out “Osama bin Laden, Osama bid Laden”, then laughed convulsively. We were taken aback, thinking that perhaps he was an adherent, or taunting us, but then we realized that he probably felt anxious to say something that he thought we could understand, and all he could think of was the name of the terrorist that he kept hearing about on his radio. It was likely an innocent expression, but we didn’t laugh with him.

After dinner on our last night, the camp manager, a charming and capable young Mongolian lady, brought her mother, who lived in the nearby nomadic community, to describe a woman’s life in Mongolia. Her mother, who was only in her mid-fifties but to me looked older, spoke no English, so her daughter translated her comments. She painted the following picture:

The four of us looked at one another in wonderment. How difficult it must be to lead such a dull and arduous life, without choices, and to candidly describe it to foreigners who have so much, which they take for granted. I hope that over the nearly two decades since my trip, life has improved for these Mongolian women.

The next morning, we took the helicopter back to Ulaanbataar, then flew on to Beijing. I was pleasantly surprised when I got to customs and a security guard took me to a storage room and returned my knife. I spent four interesting days touring the City, and visiting the Great Wall, before I was able to fly on to New York, where nothing had returned to normal.