Many American presidents have been enthusiastic fishermen. The most notable were Chester Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Dwight Eisenhower and Jimmy Carter. Quite likely, the most accomplished was Hoover and, although during his lifetime he fished in many places throughout the world, his favorite fishing haunt while he was President was his camp on the upper Rapidan River – in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, about 55 miles northeast of Keswick. The Rapidan Camp has survived to this day and is contained within the Shenandoah National Park.

The Rapidan Camp can be accessed from the Milam Gap parking area on the Skyline Drive, and walking down the Mill Prong Trail about two miles. Alternatively, one can take Route 231 through Criglersville, then Routes 670/649 to an entrance gate, and then a walk of a bit over a mile along the River (one of the best native brook trout fisheries in Virginia) to the Camp. Note that the last seven miles or so of driving up to the gate is on a narrow, rough dirt road. The last time that I was there, a couple of years ago, it had intimidating deep, wide ruts that would disable any car that slid into them. I understand that it has since been improved, but it is still very slow-going, even with a 4-wheel drive vehicle.

Building Camp Rapidan in such a remote site was a major challenge in 1929. Even traveling there by automobile to fish and enjoy the salubrious environment must have required an enormous effort, especially when the size of a President’s entourage is considered. When I first learned of the Camp, I realized that I knew practically nothing about Hoover, except that he was the President when the stock market crashed in October, 1929 – an event that ushered in The Great Depression – three words which inevitably follow the mere mention of his name. When I found that he was an avid and accomplished fly-fisherman and wrote frequently about the sport, I began to dig a little deeper.

Hoover was no anomaly, who become president by some backroom deal or a quirky primary process. He was actually an American icon, with a real “Horatio Alger” biography. His early life was the prototypical American rags-to-riches story: born in a small cabin in rural Iowa in 1874; parents both died before his 11th birthday; he and two siblings were sent off to live with three different families of relatives nearby; a year later, he and his older brother were sent to separate families of relatives in Oregon, then a very rural state with a tiny population of only about 100,000. Oregon had great trout and salmon rivers, and Hoover (called Bert) fished often, becoming an excellent angler, including with the fly. Bert was also a fine student, being selected for the initial class of what is now Stanford University, graduating in 1895 as an engineer, with a major in geology. During his college years, he camped and worked during the summers in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains on geological exploration and mining projects, sometimes with his classmate Lou Henry –a rare female geology major – whom he later married. He always carried his fishing rod, perfecting his skills by taking advantage of any free time to cast a line. After graduating, during the period 1896-1913, he and Lou traveled constantly and indefatigably, often under physically-demanding circumstances, on business to Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, New Zealand and other far-flung places, working on mining projects and, ultimately, investing in mines. Bert acquired a reputation as an intrepid traveler and an extraordinary miner and businessman, and Lou was his equal. They became wealthy – not Rockefeller-rich – but set for life.

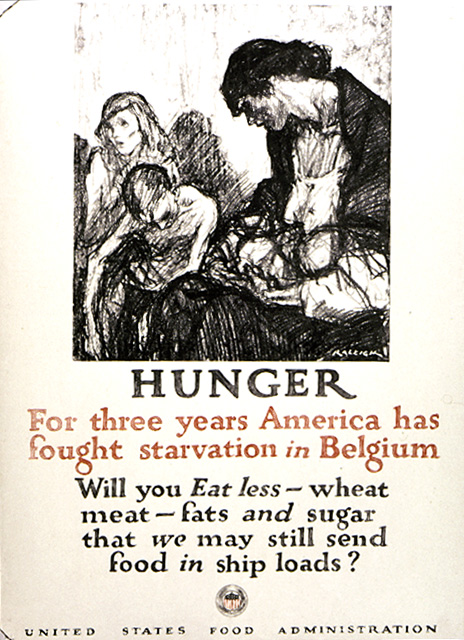

In 1914, while the Hoovers were enjoying a respite in the U.S., the war in Europe broke out, and many Americans were stranded on the Continent. An American Committee was formed in London to arrange for their rescues, and the Hoovers not only sailed to join them, but brought substantial personal funds to contribute to the effort. Bert quickly took over management of the Committee that was instrumental in rescuing over 50,000 Americans. That done, his Committee morphed into the Commission for Relief in Belgium, with a mission to save millions of Belgians starving under German occupation. Hoover’s Commission raised over $200 million from the Allies for the relief mission, at an administrative cost of less than $3 million, and not only fed the Belgians during the War, but had $24 million left over after the War for reconstruction. Based on this impressive effort, and similar work in Russia and Ukraine, Hoover became highly acclaimed in America and Europe, recognized as a gifted engineer and manager – but with a heart – as evidenced by the sobriquet commonly given to him, “The Great Humanitarian”.

When Warren Harding was elected President in 1920, he named Hoover as Secretary of Commerce. Previously the post had been of little significance, but Hoover, always independent and aggressive, made it a powerhouse, spurring the economic boom of “the Roaring Twenties.” He served in that position with distinction and without scandal (not easy in the Harding administration), and after Harding’s death, for six years under Calvin Coolidge. When Coolidge chose not to run again in 1928, Hoover was the overwhelming Republican choice, and he won the Presidency by a huge margin over Al Smith. By the time he took office in March, 1929, American economic growth had already slowed considerably, but the stock market continued to soar, as speculators ignored reality. The impending debacle was foreshadowed by the prominent financier, Bernard Baruch, who famously said:

When beggars and shoeshine boys, barbers and beauticians can tell you how to get rich, it is time to remind yourself that there is no more dangerous illusion than the belief that one can get something for nothing.

Of course, it all crashed seven months after Hoover’s inauguration, leading to ten years of the worst and most prolonged economic decline in American history. Hoover wrongfully assumed that, as in the past, a natural recovery would ensue after a few years. His laissez-faire approach and the protectionist policies (which he personally didn’t favor, but nonetheless foolishly implemented because of loyalty to the isolationist Republican Party) failed miserably, and when he ran for re-election in 1932, the economy was at its nadir with 25% unemployment, and the stock market having lost almost 90% of its value from the 1929 peak. He appeared impotent and overmatched, and was crushed in the 1932 election by Franklin Roosevelt, who confidently promised hope and change, including major new government spending programs (an anathema to Hoover) to stimulate economic activity. The economy slowly recovered under Roosevelt through 1936, with unemployment dropping to 9%, but then a severe recession hit again in 1937-38, with unemployment more than doubling and general economic conditions being nearly as bad as they were in 1933. In 1939, World War II broke out in Europe, the need to supply the Allies jump-started the American economy, and recovery from the Great Depression began. Had Roosevelt not run for a 3rd term in 1940 – an unprecedented action, breaking an American tradition dating from George Washington – his legacy might be quite different than it is today, but such are the vagaries of history.

Hoover was what today we would call a workaholic, usually putting in workdays of 12 hours or longer. But he believed that a President needed to get away occasionally for quiet, contemplative periods in order to recharge his batteries. The only leisure activity that he really cared about was fishing, and he also felt that being identified with the sport would enhance the image he sought, as that of a “common man”. In his memoirs, Hoover wrote:

Fishing seems to be one of the few avenues to be left to Presidents through which they may escape to their own thoughts, may live in their own imaginings, find relief from the pneumatic hammer of constant personal contacts, and refreshment of mind in rippling waters. Moreover, it is a constant reminder of the democracy of life, of humility and human frailty. It is desirable that the President should be periodically reminded of this fundamental fact – that the forces of nature discriminate for no man.

Shortly after his election, Hoover’s staff began exploring for a place to relax within driving distance of Washington, D.C., and the upper Rapidan was his choice. Using his and Lou’s personal funds, he acquired the land, and had the 13 rustic buildings constructed by a U.S. Marine unit. He mothballed the Presidential yacht (which held no interest for him) and transferred the crew to work there. The River in the chosen section is small, fast and subject to flooding, so he had screens put in below the Camp’s pools to retain the stocked fish, which raised the hackles on some Americans who thought that to be unsportsmanlike. In 1932, Hoover donated the Camp to the people of Virginia, for use as a future Presidential retreat. Roosevelt’s disability made the Camp impractical, so he had a new facility built at Camp David in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains, which continues to be a retreat for our presidents. The last President to use Rapidan Camp was Jimmy Carter, in the late 1970s.

The Hoovers regularly held important meetings with both domestic and foreign dignitaries on the Rapidan, though the press was rarely invited to observe – a very bad public relations decision. There was telephone service, and a plane flew over every day dropping mail and newspapers. As the Depression worsened in the early 1930s, and many Americans suffered, Hoover was often chastised for his “feckless” excursions there, a criticism which seems quaint by modern standards for presidential getaways.

When Hoover left office in 1933, his national reputation was in tatters, particularly while the Depression continued. But he soldiered on, helping manage food relief programs in Poland, then later, Finland, after those countries were invaded in the late 1930s, and then through the War’s end, and during the rebuilding of post-War Europe. When he was not working, he was fishing, typically 10-12 weeks a year for the remainder of his life. He became a keen deep-sea fisherman for tarpon, sailfish and virtually every other variety that would bite. After the strain of fighting large fish in the open ocean became too great, he switched to chasing bonefish on the flats in the Florida Keys, and became an expert at that. For his last fourteen years he fished with a prominent Florida guide, Calvin Albury, who marveled at Hoover’s fishing ability, discipline and endurance. After their last trip, Hoover at age 89 gave Albury his equipment, saying he did not expect to return. He was right, and he died within a year.

Some writers and historians conflate Hoover’s passion for fishing and his Camp with the severity of the Depression. For example, Howell Raines in his entertaining 1993 memoir, Fly Fishing Through the Midlife Crisis, which contains much to like about fishing in the American South, states that “the Marines scraped across the mountains in 1929 so that Herbert Hoover could reach the Rapidan (River). In those days the stream was reserved for his exclusive use. He also needed a place where he would not be bothered by the little people while he planned the Great Depression.” Certainly, Hoover’s policies failed in stopping or even slowing down the worsening of the Depression, but the idea that he planned it, or was even indifferent to it, is preposterous, and inconsistent with his history. Nearly all of his noble humanitarian efforts in Europe – both before and after his presidency – were on behalf of Raines’ so-called “little people”. Perhaps, had Raines written his book after his own scandalous debacle and departure in 2003 as Editor of the New York Times, he would have understood that leaders can make poor choices without being malevolent.

Hoover’s personality fit the stereotype of an engineer. He always fished in a suit with a white shirt and tie – whether alone on the Rapidan, on a mountain stream in the West, or a steaming bonefish flat. While fishing, he was laser-focused on his target and rarely engaged in idle conversation or took breaks. He had enormous energy, and would often work well into the night after fishing all day. Jimmy Carter was also an engineer, and both men failed to be re-elected, primarily because of the County’s economic problems while they were in office. They were often criticized for being too detail oriented, unable to empathize with the plight of regular Americans, and overly rigid in their thinking and approaches, but interestingly, both made greater contributions to their country and the world in their post-presidential years than the vast majority of modern presidents.

Hoover wrote numerous magazine articles about fishing and other subjects after the 1950s. Remarkably, in his 80s, he wrote his 4-volume tome, An American Epic, about the history of his country’s food relief efforts around the world during the two World Wars and their aftermaths. In the last year of his life, at age 89, he wrote his only angling book, Fishing for Fun and to Wash Your Soul, a simple volume of snippets on the rewards and frustrations of fishing. It closes with:

There are two things I can say for sure: two months after you return from a fishing expedition you will begin again to think of the snow-cap on the distant mountain peak, the glint of sunshine on the water, the excitement of the dark blue seas, and the glories of the forest. And then you buy more tackle for next year. There is no cure for these infections. And that big fish never shrinks.

Only three of Rapidan Camp’s original 13 buildings remain today. Many of the landscape features of the Camp, such as trails, pools, bridges, and a charming stone fireplace also survive. The National Park Service has restored the exteriors of two cabins to their appearance in 1932, and the interior of one. That cabin, and a museum inside a second cabin are open to the public for scheduled tours led by Park Rangers.

Herbert Hoover was a successful and exemplary American for all but four years of a very long life. But those four years, during which he made bad decisions, or maybe he was just in a hopeless place at a hopeless time, have defined his political legacy – largely cancelling out all of his good work, at least in the eyes of most Americans. Hoover failed greatly in the biggest and most important job of his life, perhaps another tragic example of Teddy Roosevelt’s inspiring description of the Man in the Arena:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.